Light skin, camera, action: Animating race

The ways in which Hollywood amalgamates – albeit uncritically and not always consciously – entertainment and pedagogy is necessary for any discussion around race on the big screen. When it comes to animation, this becomes an even larger issue. Walt Disney has long lent itself to a tradition of assuming aesthetic pleasure over critical inquiry, and Disney’s recent addition, The Princess and the Frog, is yet another example of the company’s long history of producing enchanting and “innocent” fictions that deal with race via typecasting, if they can be said to deal with race at all. From the broadly sketched black-American crows of Dumbo (1941) and the “Injun” powwows of Peter Pan (1952), working in a non-Western space is not a recent experiment in Disney films.

What is, however, is the critical material that has arisen out of a need to deconstruct Disney’s contradictory way of situating race/ethnicity in an ahistorical, apolitical realm on the basis of essential qualities. More recent films, such as The Princess and the Frog, wholly dodge the murky histories of colonization, imperialism, or race privilege – three issues that are still, in many ways, contemporary ones.

It comes down to this: Disney’s mythic power of construction makes it impossible for viewers, with or without parental guidance, to critically investigate the mode in which Disney literally draws its world and naturalizes its racial imagery without reflexively pointing to its source – a racialist Western imagination. Films like Aladdin and The Lion King feature worlds of “Other” cultures that are grossly mythologized and silenced into apolitical narratives.

The 1992 hit Aladdin, for example, takes place in the fabricated and mysterious Middle Eastern region of “Agrabah,” and by a complex chronicling of a contemporary Orientalist attitude, outlines power as available to its characters only by inherited wealth, con artistry, or the help of a genie. Never is the power of those in the Middle East real, rational, or enduring – as would be the case in, say, Canada and the U.S.

Disney’s 1994 The Lion King also locates, in the geographically displaced African space of “Pride Rock,” a family of animals who can think and speak like human beings (Disney’s first and only attempt to represent African cultures/peoples) but are nonetheless savages whose quests for power revolve around the Animal Kingdom throne. The fact that “Pride Rock” exists in a timeless place works in a similar mode to suggest that Africa might not have caught up yet to Western ideals of progress, while African cultural representations are reduced to ritualistic images, celebrations and chants.

These two films are prime examples of Disney’s desire to evade any critical representation of diversity within respective cultures and ethnic groups, a move that marginalizes racially-identifiable narrative subjects so that the films successfully reflect whiteness as the I/eye, the universal looking into these “Other” worlds. Moreover, these worlds are presented as outside of history, offering happily-ever-after fictions of oppressed peoples so as to avoid engaging in any meaningful exploration of cultural difference.

As long as Disney perpetuates this racist aesthetic, we throw the critical study of difference and the project of anti-racism to the land of make-believe. Just as the Orientalist attitude at play in Aladdin presented Western audiences with an image of the Middle East as a place of sensuality, despotism, depravity, and irrational behavior, The Lion King presents Africa to us as literally animalistic and underdeveloped: the absence of any human characters or signs of human life work to situate Africa as essentially uncivilized, and the use of non-human characters vehicles this idea without too many problems.

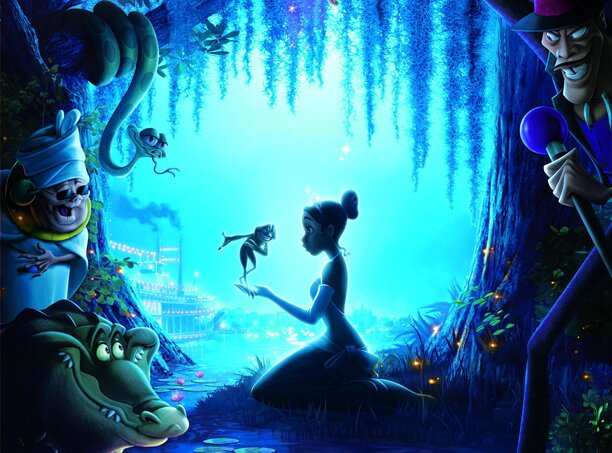

Disney’s The Princess and the Frog, considered by many to be Disney’s first Black fairy tale, is equally troubling, offering a picture of New Orleans’s French Quarter as yet another barbaric place of Black spinsters, voodoo masters, charlatans, and vagabonds. Then we are introduced to Prince Naveen, from the fictitious land of Maldonia, who is implied to have African ancestry though his light skin feels less like an attempt on Disney’s part to reflect New Orleans` legacy of miscegenation than it is Disney’s continued fear of representing Black men. In any case, Naveen is transformed into a frog by the evil voodoo (not that evil and voodoo are terms that go together) magician Dr. Facilier. He mistakes Tiana for a princess, and has her kiss him to break the spell. Not only was Tiana never meant to be our beloved Black princess, but her reign fails to flesh out – upon kissing the frog prince, she herself turns into a frog (translation: Black royalty still has to live with minority status). There is nothing innocent about racial representations in these films, and this self-confessed inability to represent Blackness is little more than a reluctance to represent Black people as people at all.

Avatar, though not a Disney film, is a more recent addition to racial politics on the big screen that warrants critique. Critics have largely hailed the film as eye-opening, a film that shows us what the earth “could have been” if indigenous peoples were allowed to thrive, while others argue that it’s a “white man’s burden” kind of film that evades any meaningful questions about race. Main character Jake is prompted to inhabit the consciousness of an avatar – a genetically engineered hybrid of human and Pandora native DNA, the Na’vi – so that he might come to understand the Na’vi ways. The irony is that the film’s grossly “inoffensive” use of graphic animation to speak on the destructive effects of colonialism doesn’t seem to faze viewers: the film has grossed over $631 million in the U.S. and Canada to become a hegemonic money-making giant of its own. Money aside, the film’s articulations of “real” people vs. the hybrid Na’vi still function to romanticize cultural and ethnic groups and place any critical enterprise off limits.

As The Lion King song goes, “there’s more to see than can ever be seen/ More to do than can ever be done.” While films like The Princess and the Frog and Avatar give us a way into critical race analysis through a mainstream channel, the challenge of color prejudice in film and media cannot be addressed by switching the racial power structure so that we might endearing rethink how bad the primitive foreigners are. Nor will it be addressed, a la 2024, by offering a heart-warming global-scale return to Africa movement. It’s about time that artistic (re)creations get political. When myth, magic, and CG win over historical and cultural accuracy, the narrative of racialized films provide no alternate intelligibility of Western racial imaginings. Cinematic enchantment comes with a high price if we assume our viewers to be culturally illiterate – that is, unable to read against Hollywood’s racialist grammar.

Author: Kirwan Institute (439 Articles)

COMMENTS