The Last Black People in America, Part I

Culture — By George Davis on February 26, 2010 at 15:21What do you do when who you are is a very difficult, but very valuable, way to be?

I went to a party in North Carolina last November to celebrate the 80th birthday of the widow of a black former sharecropper. She had raised 13 children after her husband died almost 40 years ago. I was invited by her second son who had been a Special Forces helicopter pilot in Vietnam.

I knew him because I had written about him in Until We Got Here: From “We Shall Overcome” to “Yes We Can”, my book that is now being edited for publication. As I said in my last post the “book is a nonfiction novel that focuses on truths about the African aspect of American life. I believe these are the truths that will set us free. I do not think that we can become one nation until we are free from the push and pull of guilt, on the white side, and accusation, on the black.”

African American life has been brutal and full of injustices, but it has also been wonderful. And it is the wonderful parts that both blacks and whites are, understandably, most afraid or most ashamed of.

If you just tell the story, the true story of African American life you will do so much more than just tell a story. In “Roots” Alex Haley told a simple story of his search to find the place in Africa from which he came. However, “Roots” was more than that. It was the metaphor that corrected our vision of our shared universal past.

What I attempt to do in Until We Got Here is tell a simple story of eight African American lives over the last half century. My faith is I have created a book that will be turned into a television mini-series to help correct our vision of our shared universal present, in the age of Obama.

The mother’s birthday was on a Friday evening in a rural place out near the eastern tidewater area of the state. Never in my life had I been in a room where there was a greater outpouring of love. There may have been 200 people in attendance; maybe as many as 100 were her extended family. All of the children got up and gave a story about how she had loved and protected. The in-laws spoke.

Then the grandchildren got up, and then the great grandchildren spoke. Were they great grands or great greats? I lost track because I was drawn in. I was caught up with them so I stopped taking notes. I was too busy anticipating the next expression of love and the unique, spontaneous manner in which the love would be delivered – a joke, a poem, a song, a story. It was the most touching outpouring of spur-of-the-moment affection I can remember. I wondered: Are these the last black people in America?

The second son was, as I was in my family. . .we were the wayward sons. After the birthday party, I reread the screen treatment for the television episode based on the story of the second son.

This is the text:

Opening Scene

Viewers see the son, a grown man.

Viewers see the mother’s lips against the phone mouth piece.

Obama’s words are first on the TV but then just in the air. He has won the presidency of the United States.

This is the end of a story about a stubborn 13 year old sharecropper’s son.

It flashes back to 12 or 13 and we see the boy’s day-to-day life in rural 1950s North Carolina.

We see him going to town on a bus to help with a civil rights boycott.

Cut to commercial

This is the happiest day of his life. He feels that he is doing something great. He is entering history.

He comes home. “My father beats me like a slave master beats a slave,” he told me.

“Never you get on that bus again. You gonna get the whole family killed. You gon get killed. They gon take the farm away.”

The next day viewers see his two sisters crying at the school: “Don’t get on that bus. You know what Daddy said.””

Viewers see his fear.

Viewers see his brother’s fear

Viewers see a special girl’s fear.

Viewers see him as he gets on the bus again.

He comes home. He faces a beating even more sever than the one he got before.

“Did you get on that bus” his father asks?

He doesn’t speak.

His sisters are asked.Cut to commercial

“Did he get on that bus?” The sisters are asked again.

A lump comes in the sister’s throat. A lump comes in the TV viewer’s throats.

The sisters lie. He is saved. Viewers exhale.

He goes off to live in a shack in the woods –no running water, no electricity.

This is not a racial story. This is a human story. He has to fish, and hunt. He has to know what plants he can eat. He has to get up and go to school. He falls to sleep in class. The special girl helps him with homework. She sneaks away to the shack to bring him food. They walk, talk, and dream.

Little episodes of the rest of his life play out.

He goes to college. Scenes with his father are superimposed everywhere he goes.

His father dies.Cut to commercial

He joins the military to send money to help his mother with nine kids left at home.

Viewer are led to know that he could have joined the Air Force and had an easier life. He joined Special Forces and becomes a helicopter pilot. Something else is happening with this guy. Why did he join the tough guys? Special Forces. . .the guys who fly behind enemy lines to drop flares to direct air strikes. They do bomb damage assessments and hunter-killer operations, capture and interrogate enemy combatants, rescue downed aircrews and prisoners of war, plant minefields and other booby traps.

Viewers see him in combat. They see him in a helicopter. Scenes with his father are superimposed.

He gets married. Scenes with his father are superimposed.

He gets a corporate job. The father is still there. The past is still there. The shack in the woods is still there. Camera work makes them come in at the oddest times and fade out.

Finally viewers see the 2008 election coming. He watches it. Can they turn North Carolina blue –yes, no, yes, no? He sees it as a chance, a chance for what? The election picks up steam. His excitement grows.

Viewers see election night. Viewers see the victory. His mother calls him. On the phone his mother says “See! See! See!” His dead father smiles.The End (cut to commercial)

As I said, he and I are, in different ways, our mothers’ wayward sons. We are not sure we “See! See! See!” how people can survive in America with the interconnected, interdependent love that was exposed at the birthday party. But the thing that is in them is in us too, and as unsuccessful as it might make us sometime in America, we think it is what a human being should and shouldn’t be.

Author: George Davis (14 Articles)

George Davis’ nonfiction novel, Until We Got Here: From "We Shall Overcome” to "Yes We Can" will be published in 2010. He has taught at Columbia, Colgate and Yale universities and is professor emeritus in creative writing at the Newark Campus of Rutgers University. He is author of the bestseller, Black Life in Corporate America, and the novel, Coming Home, upon which the Jane Fonda Vietnam War film is loosely based. He has been a writer and editor for Essence and Black Enterprise magazines, The Washington Post, and The New York Times.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

The next justice

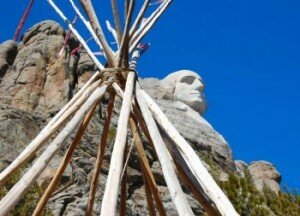

The next justice A man of great vision departs Mount Rushmore Memorial

A man of great vision departs Mount Rushmore Memorial