Policing gender and sex through sport

Featured, Sports, Women — By Rajeev Ravisankar on March 9, 2010 at 11:12In January, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) convened a so-called gender symposium in which medical ‘experts’ concluded that intersex athletes should be treated as having a medical disorder, and that eligibility of such athletes be decided on a case-by-case basis. They also suggested that photographs of athletes be taken and sent to experts to determine whether the athlete might have a “Disorder of Sex Development” (DSD) and called for the establishment of ‘centers of excellence’ to handle treatment.

Monday Aug. 17, 2009 file photo South Africa's Caster Semenya, right, competes in a Women's 800m semifinal at the World Athletics Championships in Berlin. The IAAF has asked the South African track federation to conduct a gender verification test on 800 meter runner Caster Semenya amid concerns she does not meet the requirements to compete as a woman. The 18-year-old Semenya is a favorite in the 800 meter final later Wednesday Aug. 19, 2009. (AP Photo/Anja Niedringhaus, File)

This is a response to the controversy around South African sprinter Caster Semenya. Last summer, Semenya won the gold medal in the 800 meter race at the World Athletics Championships. However, through different stages of competition she had to go through a battery of tests following doubts regarding her sex. Some of her competitors rejected Semenya as a female. Italian runner Elisa Cusman said “These kind of people should not run with us” and “For me, she is not a woman. She is a man.”

While she endured a sex determination test by doctors, Caster Semenya faced a gender identity test in front of a global audience due to the intense media obsession that developed around her. Western media sources in particular speculated about Semenya’s ‘masculine characteristics’ and ‘powerful running’ which did not fit in stereotypical and narrow representations of female athletes.

Late night talk show hosts like Jimmy Kimmel and David Letterman ridiculed her. For example, Kimmel said “if she does turn out to be a hermaphrodite, I guess that would make her hair style a herm-afro right?” and then played a clip in which kids were shown a picture of Semenya and asked to identify the runner as a man or a woman. The inability to think beyond dichotomous ways of understanding gender and sex produced attempt after attempt to define Semenya and place her identity in a box with fixed characteristics.

The confused and problematic language around this issue is easy to identify. There is the abundant use of the word disorder and reference to the term gender identity disorder. Then there is the assertion that an individual failed a gender verification test. If anything, such language is an indictment of a societal understanding that is disconnected from the reality of gender as a complex and fluid social identity and a person’s sex as something that cannot be determined by a single marker. “There isn’t really one simple way to sort out males and females. Sports require that we do, but biology doesn’t care,” says Northwestern professor Alice Dreger.

Not surprisingly, South Africans were outraged by the treatment of Semenya, which many believed was explicitly racist. In a New Yorker article titled “Either/Or – Sports, sex, and the case of Caster Semenya,” Ariel Levy draws attention to the Apartheid era racial classification that defined individuals within a hierarchy and essentially determined their representation, rights and opportunities. So this mainly Western effort to define Semenya felt familiar for South Africans who experienced categorization under white minority rule.

Locating this issue in a historical context, athletics officials have associated track and field with masculinity. According to Sport and the Color Line, Olympic governing bodies of the 1950s considered eliminating several women’s track-and-field events because they were ‘not truly feminine.’ Olympic official Norman Cox sarcastically proposed an alternative to banning events, suggesting that “the IOC should create a special category of competition for the unfairly advantaged ‘hermaphrodites’ who regularly defeated ‘normal’ women, those less-skilled ‘child-bearing’ types…”

There is also a long history of sex testing for female athletes in international competition. For many years, the test consisted of a degrading physical examination and visual inspection of the athlete. In 1968 the IOC introduced chromosomal testing due to persistent concerns that males would try to compete as women. These tests were required for all female athletes in Olympic competition until 1999, when the IOC abandoned mandatory testing and also recognized the problems with using chromosomes alone to determine eligibility.

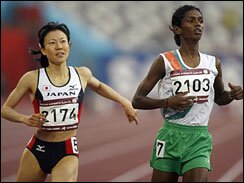

Japan's Miho Sugimori, left, and India's Santhi Soundarajan cross the finish line in heat 1 of the women's 800m event on the opening day of competition at the 15th Asian Games in Doha, Qatar, Dec. 8, 2006. (AFP/Getty Images)

These policy changes have done little to minimize the humiliation faced by athletes who are singled out for testing. Another recent example is Santhi Soundarajan, a runner from Tamil Nadu, India, who was forced to give up her silver medal in the 2006 Asian games after a test indicated that “she does not possess the sexual characteristics of a woman.” News stories screamed that she had “failed a gender test” and equated her with athletes who had used performance enhancing drugs.

Currently, suspicion of specific athletes serves as the basis for sex testing in international athletics. In addition, the move toward requiring treatment or even surgery to continue competing is a step in the wrong direction. According to Kristen Worley of the Coalition of Athletes for inclusion in Sport, “Hugely exaggerating any possible health issue enables this small group of scientists, mainly older men, to medicalise, define and control women’s health and bodies.”

While Caster Semenya’s return to competition is still in question, the role of sport in perpetuating and reinforcing the rigid two-sex system is clear. It is necessary to recognize this and shift attention to broader society. Otherwise, the politics of gender, sex and race will be contested by heavily scrutinizing individual bodies.

Tags: African, Caster Semenya, David Letterman, Gender Policy, India, International Olympic Committee, IOC, JImmy Kimmel, Olympics, Santhi Soundarajan, south asian, sport, Sports, WomenAuthor: Rajeev Ravisankar (2 Articles)

Originally from Columbus, Ohio, Rajeev received his B.A. in International Studies and Political Science from The Ohio State University. In addition to his work at the Kirwan Institute, Rajeev continues to write for The Ohio State University’s student newspaper, The Lantern, as an opinion columnist. His research interests include examining caste and class hierarchies in South Asia, the construction/deconstruction of nationalism, and the impact of neo-liberal economic policies on communities in developing countries. Also, he is interested in looking at the role of corporations in the international system and addressing the ways in which increasing corporate-control of media runs counter to democratic norms.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Done right, immigration reform will boost the U.S. economy

Done right, immigration reform will boost the U.S. economy Tracing “African-American” Across the Colorline

Tracing “African-American” Across the Colorline Emphasis 'Reinvestment' in the ARRA

Emphasis 'Reinvestment' in the ARRA Ernesto Yerena: A rising grassroots artistic force

Ernesto Yerena: A rising grassroots artistic force

1 Comment

Hey Rajeev.A good case to raise. I wud definitely want to see a blog following the future of Caster Semenya.

The sports body, IOC is hypocritical at its best and so are d players.Sports or any game is not only about winning or losing, there are a lot of values in play as well.One which is universal is respecting your co-players and competitors. M utterly disgusted at the unthoughtfulness of Italian runner Elisa Cusman who said “These kind of people should not run with us” and “For me, she is not a woman. She is a man.”

Lets just think if the investigations find Caster as right..well i cud hav penned..dat she is biologically established as a woman..bt i cant just do it..it can never cross my mind…

I mean wat will d the Italiano have to say den..can she retract to her statement n soothe Caster…

I believe IOC must invest more tym in inculcating the true values of game than ostracising the players.