Obama, racial and political complexity, and hope for a transformed racial order

Visions 2042 — By Guest Author on May 25, 2010 at 06:35By Craig Livermore, Executive Director of New Jersey Law and Education Empowerment Project

Beyond Dichotomy

A year and a half into the presidential term of Barack Obama, the hope that his election engendered has begun to face substantial obstacles. The hope of the Obama candidacy has run head on in the Obama presidency into the realities of entrenched identity interests regarding health care, education, foreign policy, and the economy. Citizens, politicians and commentators from both sides of our nation’s dichotomized political debate have expressed frustration regarding the Obama political vision in practice.

From the right, continuing cries of an overreaching federal government led by a traditionally centralizing liberal executive issue forth. From the left arise varying concerns regarding a leader who is too willing to compromise, who has not directly addressed issues of race in the manner expected, and who continues to use traditionally conservative code words such as responsibility, faith, family, and self-reliance.

Yet, the political vision and existential manifestation-as-leader of Barack Obama have remained fiercely consistent throughout both his presidential candidacy and his presidential administration. His difficulty in fitting into the American comfort zone in his presidency lies not in any mercurial addiction to political expediency, but instead is based in his complexity which is at odds with the American proclivity to view the world in bi-polar terms.

In our national consciousness, there is either progressive or conservative, Christian or non-Christian, religious or secular, elitist or populist, and, racially white or racially black. Our nation understands, of course, that in some sense possibilities exist outside of these dichotomous categories. But such dichotomies are so deeply engrained that we can only make sense by attempting to understand new possibilities by interpretation through a bipolar lens. Thus, a continuum of possibilities is inevitably simplified and distorted as square pegs are forced to fit into round holes.

As the demographic paradigm continues to shift in the United States, however, a viewing of the world in dichotomous terms will have been transformed into a broader understanding by the constitutive reality of our racial landscape, and by the nuanced racial and political vision which seeds will have been laid by Barack Obama. As we approach 2042 the United States will for the first time exist as a nation with no clear majority racial group and, by all measures, will be more diverse than it ever has been. Yet the Obama complexity vision will have launched us in a direction to elevate this reality beyond ideology. We will no longer remain beholden to political models which either comprehend racial minorities as discriminated-against victims who must fight for their rights against an entrenched and unjust majoritarian power structure, or, to the contrary, believe that any inequalities in societal outcomes (short of those dictated by overt discrimination) indicate no broader societal responsibility.

Indeed, under a complexity vision, there may be insights garnered from both sides of this spectrum, but such insights will be assimilated as deemed effective in a solutions-orientated approach which elevates the reality of egalitarian human situated-ness over political or racial ideology. Thus, in 2042, the United States will have begun to achieve concrete egalitarian results in racialized arenas such as, for example, the historical disparate outcomes among racial groups in education.

The complexity vision, seminally manifest on a broad scale by Barack Obama as the vision of his presidency will, by 2042, have grown in cultural and political influence to allow us to redefine our static notions of race, identity and politics and thus to create a more fluid understanding of group identification, while remaining doggedly committed to egalitarian principles.

Race, Politics and Complexity

When Jesse Jackson expressed his frustration, in a moment he thought to be furtive, that Barack Obama was “talking down to black people” in 2008 he was not just revealing a generational divide among the black civil rights community. He was also revealing the difference of political vision between traditional progressives like Jackson and neo-progressives such as Obama (if a label must be used). Reverend Jackson was responding to Barack Obama’s consistent practice of challenging blacks to rebuild community and return to values such as responsibility, commitment, education and family, and to not rely upon government for solutions to their obstacles.

In fact, there has rarely been an occasion in which Obama has spoken to a majority black audience, or addressed the issue of race, in which he has not emphasized the importance of renewal, self-reliance, and other values that Obama has himself termed “conservative.” From his “Race Speech” during the campaign in which he addressed the controversy regarding Reverend Jeremiah Wright, to his address at the NAACP centennial celebration in 2009, to his commencement address at Hampton University in May 2010, Obama has consistently focused upon 1) personal responsibility; 2) communal and individual strength and self-reliance; 3) the dangers and distractions of recreational technology and 4) the need for stronger family structures. As Obama proclaimed in his speech to the NAACP:

We need a new mindset, a new set of attitudes. . .Yes, if you live in a poor neighborhood, you will face the challenges that someone in a wealthy suburb does not. But that’s not a reason to get bad grades. . .No one has written your destiny for you. Your destiny is in your hands. . .To parents, we can’t tell our kids to do well in school and fail to support them when they get home. For our kids to excel, we must accept our own responsibilities. That means putting away the Xbox and putting our kids to bed at a reasonable hour.

The first line of analysis of Jackson’s response should be the realization that the black community, like all ethnic, political or religious groups, has always encompassed an interactive mélange of viewpoints. The Obama gospel of self-reliance and personal responsibility has a deeply engrained history among black conservatives from Booker T. Washington to Clarence Thomas. But perhaps the second line of analysis of Jackson’s frustration lies not in a black progressive voicing frustration with a black conservative, but in a black progressive wanting to support a black progressive presidential candidate who too often sounds like a black conservative.

Of course, Obama is not a traditional black conservative, or a traditional conservative in any sense. Before entering into the sermonic flourish on personal responsibility in the NAACP speech outlined above, Obama proclaimed “Government programs alone won’t get our children to the promised land.” But government programs will, for Obama, play an essential role in achieving greater equality.

The extreme far right of the black tradition can be seen as being embodied by figures such as Malcolm X and Marcus Garvey, who advocated complete separation from the white establishment and complete mistrust of any governmental solution due to its inevitable cooption by hegemonic interests. And although Clarence Thomas is no Malcolm X, he is not given enough credit for the perspicacious manner in which his judicial opinions voice skepticism that reliance upon judicial governmental intervention or other white power structures will yield empowering results for those of minority groups (quoting the likes of Frederick Douglas in doing so).

Thus, while Obama possesses conservative existential, political, and racial currents, he maintains an articulation of a communal polity optimism of the progressive universalist. In his speech “A More Perfect Union” given in 2008 regarding the Jeremiah Wright controversy, Obama urges blacks to understand that the path to equality “means binding our particular grievances—for better health care, and better schools, and better jobs—to the larger aspirations of all Americans.”

It is a belief in the efficaciousness of interest convergence. Certainly, Obama’s “Jeremiah Wright” speech is fecund with universalist declarations. Indeed, while showing empathy for Reverend Wright’s racial frustration, Obama describes Wright’s shortcoming as the lack of sufficient optimism and hope regarding how far American society has progressed in racial matters, and how much it has the potential to progress further in the future.

Obama also in the speech emphasizes, as he often does, his birth by a white mother, his rearing by white grandparents, and his empathies for the frustrations of those in the white working class. But one cannot help but to suspect that, at least in some manner, the pragmatism for which Obama is famous is at play in his interest convergence approach in the sense that he appears to both strive for universalism, and to remain completely race conscious.

It is not only black progressives which have felt some frustration with President Obama’s complexity. Progressives of all races have voiced concern that the President has been too compromising, and/or too unwilling to voice vehement opposition to conservatives, in foreign policy, the healthcare debate and education.

Political commentator David Brooks has written in the New York Times regarding the inability of the right and the left to “Get Obama Right,” and thus for both sides to feel frustration as a result of misapprehension. Consider education. No one with an appreciation of reality could admit that the United States does not continue to face extreme problems with inequitable differentials of educational attainment among racial groupings. Traditional progressive attempts to remedy educational disparities have sought to seek greater levels of racial integration in education or fight for equalized spending between wealthier and poorer school districts.

However, the educational policy initiatives of the Obama administration have emphasized competition, accountability for teachers, schools, districts and states, public school choice, assessment standards, and merit-based teacher pay and hiring decisions. Such language and principles are undeniably those of the market, a province whose inclusion in educational discussions has always created considerable discomfort among liberals. But again, President Obama proposes the addition of flexibility in assessment, and considerably more federal funding for education, as reforms for No Child Left Behind, both of which keep him safely far a field from traditional conservative territory.

Racial Equity in 2042 Through Shared Complexity

President Obama embodies an existential, political, and racial complexity which will provide the paradigm necessary for our nation to evolve as it becomes an increasingly diverse nation into the middle of the 21st Century. Yet Obama’s complexity, and the concomitant necessary paradigm, is founded upon a fiercely consistent vision. The paradigm is nowhere near a post-structural relativism that would lack the moral power to impel us forward.

The Obama vision is able to comprehend the endemically “conservative” elements and moral language of the black tradition, which is shared by large portions of increasingly prevalent minority groups from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East and Asia. It is founded on an unwavering egalitarian belief that all racial groups can succeed when properly supported by the community and when each group takes sufficient responsibility for its own destiny. And it is a being-in-the-world which has the courage to soften the solidification of its own identity, in order to incorporate elements from various groups that can lead to pragmatic solutions to problems of inequity.

The racial and political climate of 2042 will feature much greater appreciation for the complexity within, and among, racial groups. In the year 2042 race will be less important, because it will be more important, and more fully understood. Once we get beyond our reified and stultifying assumptions of identity-based categories it is only then that we will truly access that which we share.

Such a racial landscape is based upon a universalism—but it is based upon a universalism keenly aware of the dangers of allowing only the dominant and most powerful group(s) to define that which is universal. Because identity-based ideology will have yielded, in large measure, to pragmatic solutions, the educational disparities among races will have been reduced significantly. Our nation will look back to the election of our first black President, not only as a vindication of progress previously made in matters of racial justice, but also as the seminal symbolic incarnation of a manner of being with the integrity to live and lead complexly with a consistent egalitarian vision.

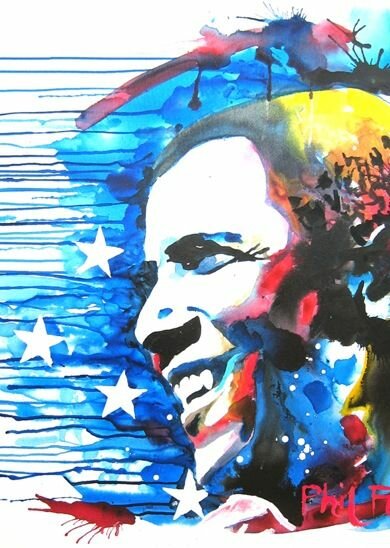

Artist: Phil Fong

###

Craig Livermore, JD, MTS, is the Executive Director of NJ LEEP (New Jersey Law and Education Empowerment Project). He is also the Board Chair of Newark Legacy Charter School and is an adjunct faculty member at Seton Hall Law School where he teaches courses on race, law and education, and legal theory.

Tags: Barack Obama, Obama, Poverty, Racial Equity, Talking about RaceAuthor: Guest Author (94 Articles)

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

The house on Imperial Avenue

The house on Imperial Avenue About those Whites-only scholarships

About those Whites-only scholarships ARRA – One Year Later: What happened?

ARRA – One Year Later: What happened? Sometimes the rainbow is not enuf

Sometimes the rainbow is not enuf