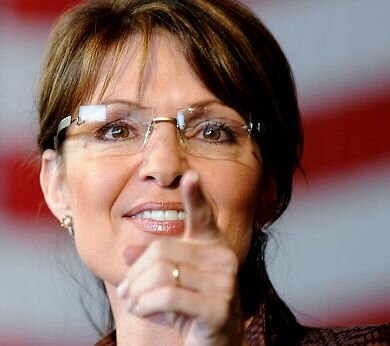

President Palin?

Politics, US — By Richard Albert on May 28, 2010 at 10:14When Republican presidential nominee John McCain announced his vice presidential running mate in the summer of 2008, his choice was greeted with equal servings of curiosity and enthusiasm.

Movement conservatives saw the selection as a game-changer: the little-known vice presidential nominee brought youth, charisma, and energy to the Republican ticket and would give McCain a much-needed boost in the presidential election. For its part, the Obama campaign scrambled to assess how the choice would affect its standing in the polls. But everyone—media outlets, politicians, Republicans and Democrats alike—all asked the same question: Who is Sarah Palin?

The initial curiosity quickly turned into skepticism about Palin’s qualifications. Her thin political resume collapsed under the pressure of intense media scrutiny. And perhaps with good reason: she had served only as a city councilor, then mayor, of a small city in Alaska, and then as Governor of the state, for fewer than two years, by the time she had been nominated for the vice presidency.

The consequences of a vote for McCain were not lost on voters. Had McCain won the presidential election and later suffered an illness that prevented him from fulfilling his duties as president, the former Governor from Alaska with no demonstrable proficiency in public policy and even less experience in foreign affairs would have become president.

McCain’s choice of Palin points to one of the biggest problems in American presidential politics today: the vice presidential pick rests on the shoulders of one person and no one else. The vice president takes office—and accepts the vast power it confers upon its occupant—not at the invitation of the people but instead on the whim of a presidential candidate. There is nothing resembling any measure of popular input or consent in the vice presidential choice because it is the exclusive prerogative of each party’s presidential nominee.

The regrettable result is to distort the incentives for picking vice presidents. Rather than selecting a vice presidential nominee who is prepared to assume the presidency, a presidential nominee is more likely to pick a running mate for politically expedient purposes of ticket balancing. This current practice threatens to leave the United States with a novice on deck, one who may be unqualified to competently discharge the increasingly important duties of the vice presidency. Worse still, the vice president may be ill-equipped to lead the nation in the event of presidential disability or vacancy.

This has not always been a problem. For most of American history, vice presidents have been consigned to a largely ceremonial role devoid of any real involvement in the functioning of government and the elaboration of national policy. So, perhaps understandably, the vice presidency has long been an easy target for critics, with many questioning the relevance of the office and others viewing it with pity and derisory humor.

For instance, John Adams, the nation’s first vice president, felt powerless and often ignored in his office. He referred to the vice presidency as “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.” One hundred and fifty years later, little seemed to have changed when Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s understudy, John Nance Garner, remarked that accepting the vice presidential nomination was “the worst damn fool mistake I ever made.” In the 1960s, President John F. Kennedy commented that his vice president, Lyndon B. Johnson, had “the worst job in Washington.” When Johnson later succeeded to the presidency, he could not help but follow Kennedy’s example of casting shame on the vice presidency. And as recently as the 2004 presidential election, Senator John McCain conveyed a similar lack of enthusiasm, likening the vice presidential nomination to being “fed scraps.”

But not anymore. No longer is the vice president a mere minion wielding only negligible influence upon the organs of government. The vice presidency now holds prime ministerial dominion in America, commands transnational authority and has, in modern times, been an almost-certain springboard to the presidency.

In light of the revolutionary transformation of the vice presidency, the office can no longer defensibly remain the choice of the presidential nominee alone. The United States must democratize the vice presidency with some form of popular consent.

There are many ways to do this. One way is to conduct separate vice presidential primaries, either before, during, or after the presidential primaries. Another option is to allow the party membership to elect the vice presidential nominee at the presidential nominating convention. Still another alternative to bestow upon the vice president the personal mandate that is currently lacking would be to subject the nominee to congressional confirmation, much like Cabinet secretaries must now be confirmed by the Senate. One could also imagine a national vice presidential election conducted on the same day as the presidential election.

These are only a few suggestions meant to begin a broader conversation about how to enhance the democratic bona fides of the vice presidency.

For it is shocking that the voice of the American electorate is silent on who should manage the power of the vice presidency. And it is even more shocking that it is instead the victorious presidential nominee—and he alone—who decides who will be the nation’s second-in-command. In a liberal democracy, it is wrong that a choice of such colossal import turns on the caprice of one individual.

The existing method of vice presidential selection is therefore perilous, to say the least. Not only does the vice presidential nominee lack the popular legitimacy that can come only from the freely given consent of voters, but nothing prevents a presidential nominee from choosing a running mate on the basis of politics and optics rather than competence and leadership. Surely the American people deserve better. The public trust commands no less.

Photo: Beck/Getty

Tags: Barack Obama, John McCain, Politics, President Obama, Sarah Palin, vice presidencyAuthor: Richard Albert (12 Articles)

Richard Albert, a graduate of Yale, Oxford, and Harvard, is an Assistant Professor at Boston College Law School, where he specializes in constitutional law and democratic theory. He writes about constitutional politics, the separation of powers, the role of courts in liberal democracy, and religion in public life.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

We invite the naysayers to join us in promoting unity

We invite the naysayers to join us in promoting unity Claim of Cuban racism rejected

Claim of Cuban racism rejected Transparency as a tool for reform

Transparency as a tool for reform