Back to the future in education reform

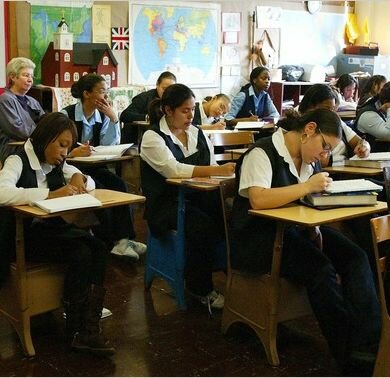

African Americans, Featured, Racial Equity — By Faye Anderson on June 14, 2010 at 05:50Back in the day, schoolchildren celebrated the end of the school year by singing, “No more pencils. No more books. No more teachers’ dirty looks.”

With states and cities threatening layoffs, teachers may soon be giving their principals dirty looks.

The teachers unions and their congressional allies are pushing for passage of a $23 billion fund that would save up to 300,000 education jobs nationwide.

With growing voter concern about government spending and deficit hawks squawking, the Education Jobs Fund will likely not be included in an emergency supplemental appropriations bill.

In any case, a teacher bailout with no strings attached would represent a missed opportunity to reform union seniority rules. The “last hired, first fired” rule consigns Digital Age children to classrooms with teachers with 20th century skills.

The New York Times reported:

Schools across the city are bracing for layoffs as city officials estimate that as many as 4,400 teachers could lose their jobs, victims of budget problems in the city and state stemming in part from the recession. Barring any rescue plan from City Hall, Albany or Congress, the job losses, expected to be announced this week, would be the first major cut to the city’s teaching force in more than three decades.

But the schools that are likely to feel the layoff pain most acutely are the hundreds of new small schools that have been a cornerstone of Chancellor Joel I. Klein’s efforts to overhaul the city’s public education system. Because of seniority rules dictating who gets laid off first, the small schools stand to lose a disproportionate share of teachers.

I am a product of the New York public schools, but union seniority rules are not unique to the Big Apple. That’s why I kept raising the issue at the recent charrette on education reform organized by DeWayne Wickham, the director of the Institute for Advanced Journalism Studies at North Carolina A&T State University.

Modeled after the annual conference for the study of the “Negro Problem” that Dr. W.E.B. DuBois convened at Atlanta University, the charrette brought together African American leaders, including Dr. Mary Frances Berry, the Rev. Al Sharpton, former NAACP president Kweisi Mfume and futurist Nat Irvin II, to identify solutions to close the black-white achievement gap.

Wickham observed, “We have a troubled public education system and its ripple effects that are particularly devastating on African American children and adults.” He encouraged the eclectic mix of scholars, educators, advocates and journalists to “think outside the box about the problems and the solutions.”

The participants agreed the problems have been researched ad nauseum. So, the focus was on identifying effective solutions.

For more than 50 years, a lot of smart folks have thought about education reform. Fifty years later, education reform has failed to close the achievement gap or reduce the pushout rate. And there are nearly 2,000 “dropout factories” – 12 percent of the nation’s high schools – where fewer than 60 percent of students who start as freshman make it to their senior year.

According to the Alliance for Excellent Education, 28 percent of the nation’s students of color are enrolled in one of these dropout factories. These lowest-performing schools account for 58 percent of black high school dropouts.

It’s time to go back to the future circa the 1960s. Back then, educators like Mrs. Williams, who taught at P.S. 3 in Bedford-Stuyvesant, knew what worked – qualified teachers, high expectations, parental involvement and community schools.

Dr. Berry stressed the “need to look at the fabric of what’s going on in the community…It depends on what’s happening in the schools and what is happening in the surrounding community.” She noted that studies show academic achievement doesn’t improve with charter schools or vouchers. Instead, they’re “a political solution not a reform initiative. They’re not performing any better than the schools they were intended to reform.”

Rev. Sharpton agreed that “the whole community does matter. Parents have to be engaged, empowered and not dismissed.”

Futurist Nat Irvin reminded us that “the future may be closer than you think it is.” Indeed, the Class of 2020 will be entering second grade next fall.

With that in mind, the black leaders issued an urgent call to action:

For all of these reasons, we call for the convening of a national charrette on the problems of black schoolchildren that will bring a broad cross-section of stakeholders together to design a comprehensive rescue plan

We believe a gathering of people with diverse backgrounds, professional expertise and shared concerns can produce the synergy that’s needed to end the black education crisis. And we urge that such a meeting be convened soon so a community-based quest for a solution to this problem can begin in earnest.

Let’s be clear: The national convening is not about more talk. Rather, it is about mobilizing catalytic leadership to inspire stakeholders to focus like a laser on the crisis of black public schoolchildren.

The future has arrived. It’s time to get back to what works.

Tags: African-Americans, blacks, Community Schools, Dropout Factories, Education, Education Jobs Fund, Education Reform, equity, race, Racial EquityAuthor: Faye Anderson (9 Articles)

Faye M. Anderson, a public policy and social media consultant, focuses on the intersection of technology, public policy and civic engagement. Faye is the founder of Tracking Change Wiki, an online platform to promote accountability and engagement in the policymaking process. As a citizen journalist, Faye provides fact-based commentary and curates links to news and information that resonate with African American readers, political influentials, thought leaders and activists. Faye’s writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, USA Today, and Stanford magazine, among other publications. She has a JD from Stanford Law School, a BA from the City College of New York, and a Certificate in French Proficiency from the Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, Sénégal.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Not everybody loved hominid fossil “Lucy”

Not everybody loved hominid fossil “Lucy” Outcry for Obama to lead the race discussion

Outcry for Obama to lead the race discussion Her gifts made room for us: The visionary pragmatism of Dr. Dorothy Height

Her gifts made room for us: The visionary pragmatism of Dr. Dorothy Height