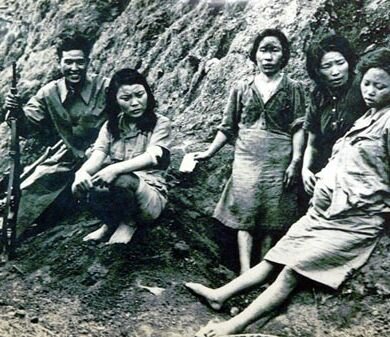

The pained legacy of comfort women

Featured, Women — By Guest Author on June 24, 2010 at 06:46By Patricia F. R. Cunningham II, Graduate Associate, Office of Minority Affairs, The Ohio State University

“Those who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” George Santayana.

In the course of history, there comes a point where we must reconcile two series of events and see how they are linked to one another. There are many scenarios, which with full disclosure demonstrate the course of human events where we, as a series of communities, make mistakes. One of the biggest mistakes of the 20th century is allowing slavery to be reintroduced in new forms.

In 1932, Japanese Lieutenant-General Okamura Yasuji was seeking a solution to the random raping of women by Japanese soldiers. He placed a request for ‘comfort women’ to be sent to Shanghai for his troops. Comfort women could be found at ‘comfort stations’ managed regularly until the end of World War II. At a comfort station or house, a soldier would pay a fee, obtain a ticket and condom and proceed to a woman’s room.

Following the second Sino-Japanese war, these houses were installed in occupied lands – 80,000 to 200,000 comfort women from Korea and others from China, the Philippines, Burma, Indonesia and Vietnam were enslaved.

Women would not only become sterile from repeated rapes, but many who became pregnant or infected with a sexually transmitted disease were given an antibiotic that would make their bodies swell and induce abortion.

Why were comfort stations created? Several suggestions reoccur that scholars agree upon: to increase the morale of the troops; to prevent their soldiers from raping women in territories they controlled; to more efficiently prevent spread of STDs; to prevent leakage of military secrets. None of these reasons justify what happened; but instead, provide poor excuses.

In 1990, almost 40 women’s groups in Korea petitioned the Japanese government to admit that Korean women were forced to be comfort women; to publicly apologize with full disclosure; to raise a memorial to honor those forced into sexual slavery and to serve as a reminder; and to provide monetary reparations and record these facts to be included in historical curricular education. The government denied their petitions and allegations. In 1991, three former Korean comfort women filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government.

A Japanese history professor at Chuo University in 1992 found documents that proved that the Japanese military forces had operated ‘comfort stations’. These findings were published in various newspapers and the government admitted its involvement.

In 2001 a conference on “Japanese Crimes Against Humanity: Sexual Slavery and Forced Labor” was held in Los Angeles, CA. Japanese researchers delivered papers claiming Japanese military, government and industry were involved in the decision to provide sex slaves for soldiers. Su Zhi Liang, a history professor from Shanghai Teachers University, noted an earlier estimate by a United Nations human rights agency was conservative. Liang determined at least 90 sex stations, each with about 500 women, operated in Shanghai alone.

The construction and government sponsorship of comfort houses has become public knowledge as survivors have come forward, groups have been founded and research performed, but that knowledge has not been used to prevent these kinds of atrocities from happening again in other forms.

What happened to comfort women would be human trafficking today. Human trafficking is still as silent, but even more pervasive, and includes young male and female children as well as adolescent females. In the past ten years, governments including the United States, formally organized and questioned other nations’ contributions to modern slavery.

Human Trafficking is modern slavery. It is the second largest and fastest growing criminal industry in the world. Victims are forced into labor, services, or the commercial sex industry in order to generate money from their labor and sex acts.

The United States has issued an extensive report that frames and defines human trafficking or “trafficking in persons” into eight categories: forced labor, sex trafficking, bonded labor, debt bondage, involuntary domestic servitude, forced child labor, child soldiers and child sex trafficking. UNICEF reports that as many as two million children are part of the global commercial sex trade. Methods of control include beatings, rapes, lies and deception, threats of serious harm or the seduction of educational attainment. These same methods were used on comfort women.

Economics links chattel slavery, comfort women and modern slavery. During the last thirty years the dominant area for recruiting child slaves and sex slaves has shifted rapidly from one country experiencing economic depression to another. During the 1970s, traffickers targeted girls from Southeast Asia, especially Thailand and Vietnam, as well as the Philippines. It took a decade for the shift to focus on Africa. Young girls from Nigeria, Uganda and Ghana flooded the international sex trade and child market. During the 1980s and 1990s, Latin American girls from Brazil, Mexico, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador became the source of wealth.

Traffickers move opportunistically to prey on vulnerable populations. In the 1980s, the trafficking out of Eastern Europe hardly registered on the radar screen. Following the economic and political collapse of the Soviet Union, the situation changed dramatically. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates since 1991, roughly a quarter of a million females were trafficked within Europe from East to West. With ethnic cleansing and social and political strife currently in Kyrgyzstan, this could be the place to watch for a rise in human trafficking.

Slavery indisputably had a role in shaping the United States. Its scars are still found as remnants in legislation, commerce and institutionalized racism. Lessons from the shameful past apparently were not learned effectively to function as a preventive historical narrative. The United States government found itself again having to be decisive about its response to comfort women and human trafficking.

The 105th Congress drafted and submitted a resolution that included the plight of women who experienced these atrocities. In 1997, Rep. William O. Lipinski submitted a powerful resolution which expressed, “the sense of Congress concerning the war crimes committed by the Japanese military during World War II.” It described how, “The Government of Japan deliberately ignored and flagrantly violated the Geneva and Hague Conventions and committed atrocious crimes against humanity.” And, it included brief descriptions of the “enslavement of millions of Koreans and forcing hundreds of thousands of women into sexual slavery for Japanese troops.” As well as “refusal by the Government of Japan to fully acknowledge its crimes or to compensate its victims.”

The resolution asked the Government of Japan to formally issue an apology for its war crimes and immediately pay reparations to victims.

Japan’s past is the precedent for today’s understanding of humanitarian issues and sexual violence in social conflict and war in countries all over the world. In order to prosecute and stop sexual violence in the present and future an understanding of devastation in the past and recognition of the use of sexual violence, enslavement, and exploitation must occur.

Japan’s wartime military comfort women houses’ are the modern precedent for issues of sexual slavery, sexual violence in war and human trafficking. This is evident in compromised countries -Bosnia, Rwanda, Nicaragua, Sierra Leone, Darfur, and Burma. The truth is, human trafficking occurs in the United States and many countries in Europe; no nation is innocent.

The United States State Department estimates 14,500 to 17,500 foreign victims are trafficked into the US each year. There are more than 27 million slaves in the world today. Something has to be done; not just by world governments, but in our everyday lives. How can we take action?

Time is essential in getting vulnerable populations the support they need, it is also what each aware person can give. Giving time is the most effective method of being involved with a movement to end modern slavery. It takes time to acquire knowledge. By reading websites like Notforsalecampaign.org and others committed to ending slavery, we can all learn about current struggles happening all over the world. Then, there is advocacy; make choices as global citizens to lend fiscal support and tell others people about travesties occurring in the United States and around the world. A Negro Spiritual reminds us that time does not wait for hesitation. Liberation of children and women is not a time to hesitate.

It’s gettin’ late in the evenin’

The sun’s goin’ down

The time is right

To get in a hurry

And do it now.

###

Filipino Comfort Women Still Struggle for Justice from Bulatlat on Vimeo.

Bibliography:

Destefano, A. (2007). The War on Human Trafficking: US Policy Assessed.

King, G. (2004). Woman, Child for Sale: The New Slave Trade in the 21st Century.

Yoshimi, Y. (2000). Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery in the Japanese Military During World War II.

Author: Guest Author (94 Articles)

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Prisoners should have right to vote

Prisoners should have right to vote Dee Brown’s book on its 40th anniversary

Dee Brown’s book on its 40th anniversary Before you convict Lawrence Taylor for rape, consider this

Before you convict Lawrence Taylor for rape, consider this Race and the law in the age of Stevens and Sotomayor

Race and the law in the age of Stevens and Sotomayor