The Sit-Ins Remembered: A fight for much more than a hamburger

Talk About Race — By Hasan Kwame Jeffries on February 1, 2010 at 05:08Exactly fifty years ago, on Monday, February 1, 1960, Joseph McNeil, David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Ezell Blair, Jr., four freshman at North Carolina A & T, an historically black college in the heart of Greensboro, North Carolina, refused to leave a lunch counter at a downtown Woolworth’s department store after being denied service because of their race in accordance with local custom and law.

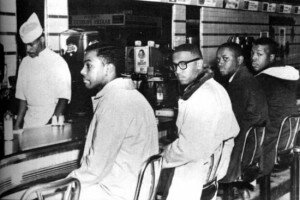

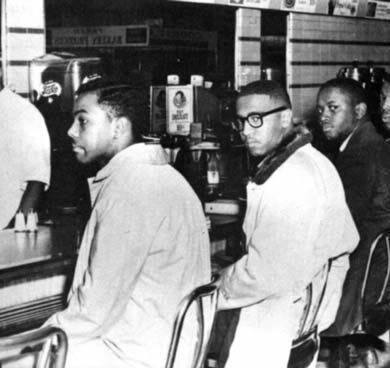

On the second day of the Greensboro sit-in, Joseph A. McNeil and Franklin E. McCain are joined by William Smith and Clarence Henderson at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. (Courtesy of Greensboro News and Record)

It was a bold act of defiance, bold because African Americans in the South had been murdered for much less than challenging racial segregation at a lunch counter. The willingness of these four young men – ‘the Greensboro Four’ – to defy Jim Crow publicly inspired their generation. Within days, several hundred students from the area’s black colleges and high schools were sitting-in at Woolworth’s, and within weeks, African American students across the South were sitting-in at segregated facilities. By the end of the year, more than fifty thousand students, mostly African American and mostly in the South had taken part in the sit-ins.

Miss Ella Baker, the guiding force behind the most daring civil rights organization of the Sixties, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which came into being as a direct result of the sit-ins, explained shortly after SNCC’s founding meeting that the sit-ins were “concerned with something much bigger than a hamburger or even a giant-sized Coke.” The students, she said, were “seeking to rid America of the scourge of racial segregation and discrimination — not only at lunch counters, but in every aspect of life.”

During this decade, we will commemorate the fiftieth anniversaries of numerous civil rights events, from the 1961 Freedom Rides and the 1963 March on Washington, to the 1964 Freedom Summer and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery March. As we do, it is imperative that we keep in mind Miss Baker’s observation. African Americans who risked their lives and livelihoods fighting to end racial segregation, whether it existed in law or common practice, did so because they wanted to enjoy their freedom rights – the wide range of civil rights guaranteed by the constitution and the full spectrum of human rights granted by God.

African Americans wanted more than to be able to eat at the restaurant of their choice or to sit wherever they wanted to on a bus. They wanted, fought for, and died for, full access to the ballot box; first-rate schools for African American children (and for many it didn’t matter if these schools were all-Black or not); unrestricted access to quality and affordable housing and health care; equal employment opportunities; and an end to racial terrorism, whether emanating from the Klan or the police.

Fifty years after the sit-ins, far too many people, African Americans in particular, and poor people and people of color in general, are denied their freedom rights. Far too many, whether because of circumstance or happenstance, are unable to send their children to decent schools, unable to find gainful employment, and unable to afford health care.

On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Greensboro sit-ins, those committed to a just and equal society ought not simply reflect on the protests of the past, but should instead work with renewed vigor toward making the unrealized goals of a half century ago a reality. Just as the Greensboro Four sat down and changed the world around them, we need to stand up and do the same today.

Tags: African-Americans, blacks, greensboro four, jim crow, protest, race, racism, sit-inAuthor: Hasan Kwame Jeffries (9 Articles)

Author of "Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama's Black Belt." Hasan is an associate professor of African American history and holds a joint appointment with the Kirwan Institute and the Department of History. Dr. Jeffries specializes in twentieth century African American history and has an expertise in the Civil Rights-Black Power Movement. His current book project investigates the African American Freedom Struggle in Lowndes County, Alabama, which gave birth in 1966 to the Lowndes County Freedom Party, an all Black, independent, political party that was also the original Black Panther Party. His recent publications include "SNCC, Black Power, and Independent Political Party Organizing in Alabama, 1964-1966," which appears in the Journal of African American History (Spring 2006). Dr. Jeffries has received several fellowships in support of his research, including a 2007-2008 Ford Foundation Post-Doctoral Fellowship. Prior to arriving at The Ohio State University in 2003, he was a Bankhead Fellow in the History Department at the University of Alabama. Dr. Jeffries earned his B.A. in History from Morehouse College in 1994, and his M.A. and Ph.D. in African American History from Duke University in 1997 and 2002.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Harry Reid was (mostly) right... Until now

Harry Reid was (mostly) right... Until now The Border Network for Human Rights: Building an immigrant movement in the besieged borderlands

The Border Network for Human Rights: Building an immigrant movement in the besieged borderlands

2 Comments