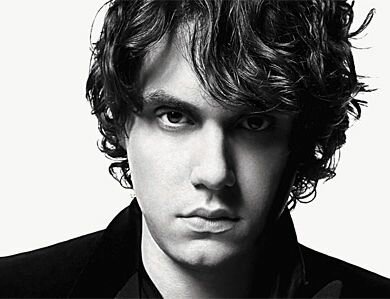

John Mayer’s longing for blackness is a”Very” wide-open window into U.S. race relations

African Americans, Featured, Pop culture — By Mikhail Lyubansky on February 12, 2010 at 07:30If you haven’t yet seen John Mayer’s interview with Playboy, well, all jokes about “reading Playboy for the articles” aside, you really should just pause here and check it out, because the interview is really very “very”. Trust me, this will make sense once you read it. Go ahead…this blog isn’t going anywhere.

Are you back? Did you remember to bring your “hood pass”? I hope so, because that’s where we’re going today. We have to. That’s where Mayer went.

But before I get to the analysis, I want to be clear about my purpose here. In regard to Mayer, I’m neither a fan, not a hater. To be honest, I don’t listen to much music (and still haven’t heard Mayer’s) and had no opinion of Mayer one way or another before reading the Playboy interview. My purpose, then, is neither to defend him nor smear his reputation. His comments inspired me to write, not because they came from John Mayer’s mouth, but because I found them to be refreshingly honest. As such, they say as much about contemporary race relations as they do about Mayer himself. It is this window into our racial Zeitgeist that interests me. So, without further ado, let’s get to the “hood”.

If you aren’t up on U.S. slang, a “hood pass” (more often called a “ghetto pass”) is usually a verbal expression of approval by a person of color toward a white person. It is intended to convey that the white person has enough positive rep or credibility to come to “my” neighborhood and hang out with “my” people. It’s a nice compliment because it signifies acceptance and trust, but, of course, it has absolutely no meaning to anyone other than the person giving out the “pass” and the one receiving it, at least not for those of us without Mayer’s fame.

For most of us, the “pass” is obviously not anything tangible that one could, you know, keep on hand in case of a heated inter-racial exchange, but for Mayer it actually signified “group” endorsement, something that not only had symbolic meaning but also meant opportunities to perform with a variety of Black hiphop artists and sell albums across the racial divide. All this is to say that Mayer had good reason to bring up his “Black credentials”, but of course he doesn’t just bring them up:

MAYER: Someone asked me the other day, “What does it feel like now to have a hood pass?” And by the way, it’s sort of a contradiction in terms, because if you really had a hood pass, you could call it a nigger pass. Why are you pulling a punch and calling it a hood pass if you really have a hood pass? But I said, “I can’t really have a hood pass. I’ve never walked into a restaurant, asked for a table and been told, ‘We’re full.’”

Mayer took a lot of heat for the N-word, and rightly so. One of the ways that our racial climate has changed is that young white people are much more cavalier about using the N-word than they were 10 years ago. This despite the fact that the NAACP took the highly unusual step of burying the word back in 2007.

The NAACP response was motivated in large part by the comments of another celebrity, Seinfeld actor Michael Richards, who used the N-word repeatedly during a comedy routine to insult members of his audience (it wasn’t part of his act). Mayer’s comments were clearly different. He wasn’t insulting anyone but rather lamenting that, even as an honorary member of the Black community, he still didn’t have full access to all its privileges.

This longing for full membership, though not often publicly voiced, is, I think, commonly felt among younger white men and women, especially by those who are attracted by, and identify with, various aspects of hip-hop culture. Despite the NAACP’s symbolic funeral, many African Americans who identify with hiphop continue to use various iterations of the N-word to express affection and solidarity. To white observers, it often seems to be a powerful bond, a bond that they know they can’t access. And as they might long to learn a secret handshake or sign, they long to be allowed into this particular exclusive club. Indeed, they might even see full membership as their right. After all, they reason, did they not already prove their worthiness by embracing Black culture?

At its worst, this longing for full acceptance manifests itself as privilege, a belief that one is entitled to the use of the N-word, but with no appreciation for the impact that word has on people in general and, given the history of U.S. racism, the differential impact of a white person using it compared to a Black person. Mayer doesn’t express this level of privilege. To the contrary, he readily acknowledged that he benefits from his whiteness (in getting service at a restaurant), but he still can’t let go of his longing, which he justifies by giving himself a little blackness:

MAYER: What is being black? It’s making the most of your life, not taking a single moment for granted. Taking something that’s seen as a struggle and making it work for you, or you’ll die inside. Not to say that my struggle is like the collective struggle of black America. But maybe my struggle is similar to one black dude’s.

If it seems like I have a problem with the above comparison, I don’t. I actually kind of resonate with his definition of Blackness. No doubt, I long for full membership too. It’s not that I want to use the N-word (I wouldn’t use it if I could), but I’d sure enjoy the assumed trust and camaraderie.

That’s my point: The longing that Mayer gave voice to is, I think, quite common, and though I find his choice of words insensitive and offensive (and by the way, this isn’t the first time that Mayer has been accused of “accidental racism“), I think the underlying feelings and needs are a great window into one particular aspect of our racial society.

His comments about Black women are telling too, but I’m going to leave that for another day.

_______________________

For more racial analysis of news and popular culture, follow Mikhail on Twitter.

Tags: hood pass, John Mayer, Mayer, Playboy interview, race talk, racism, Talking about RaceAuthor: Mikhail Lyubansky (24 Articles)

I'm a member of the teaching faculty in the department of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where I teach, among other courses, The Psychology of Race and Ethnicity. My research and writing interests focus on immigration, racial/ethnic group relations and social justice. I write a blog about race and racial issues for Psychology Today. Please follow me on Twitter: http://www.twitter.com/mikhaill (@mikhaill)

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Israel, ideology of trauma

Israel, ideology of trauma Why the Conservative Party?

Why the Conservative Party? Take no prisoners: The policing of black girls

Take no prisoners: The policing of black girls

2 Comments

i found the comment about having a Benneton heart and a David Duke penis quite enlightening. This comment told me alot about who he really is.

I find it interesting that you chose to successfully defend his use of the N word ( that part I found least offensive) but completely steered clear of his racist expression towards Black women. And no I don’t fault John for not dating Black women, everyone has their preferances , but his heavily coded words revealed a deeply racist person and people like you are turnng a blind eye.