Africville apology is a start, not an end

Featured — By Mike Barber on March 1, 2010 at 05:36Last week’s apology by city of Halifax Mayor Peter Kelly, for the evictions and razing of the African-Canadian community of Africville in Nova Scotia during the 1960s, marks a small but significant moment in the history of slavery and racism in Canada. The official apology issued February 24, 2010, made on behalf of Halifax Regional Council and Halifax Regional Municipality (HRM), was accompanied by terms of the 2005 agreement reached between the municipality and the Africville Genealogy Society, which, along with a formal acknowledgment of loss, included:

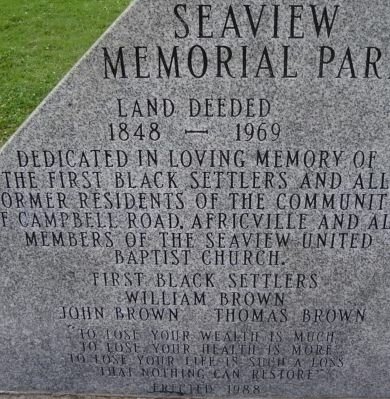

- $3 million (CAN) contributed towards the reconstruction of the Seaview United Baptist Church which will serve as a memorial to Africville;

- 2.5 acres of land at Seaview Park to be provided to the Africville Heritage Trust Board;

- a park maintenance agreement to be established between Africville Heritage Trust and HRM for the lands known as Seaview Park;

- and, the establishment of an African-Nova Scotian Affairs function within HRM

Roots in slavery and war

Africville’s roots go far back to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) when approximately 3,500 Black Loyalists (free or former enslaved African-Americans who escaped to the British side of the conflict) migrated to Nova Scotia, many of whom fought for the British in return for the promise that they would not be allowed to be enslaved. Slaveholding Anglo-American Loyalists also migrated to Nova Scotia bringing with them about 2,500 enslaved African-Americans. But unlike their free counterparts, these African-Americans remained enslaved until the practice of slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834—meaning, for a few decades, Nova Scotia simultaneously had two distinct Black populations: one whose freedom was protected, and the other whose enslavement was sanctioned.

Africville’s roots go far back to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) when approximately 3,500 Black Loyalists (free or former enslaved African-Americans who escaped to the British side of the conflict) migrated to Nova Scotia, many of whom fought for the British in return for the promise that they would not be allowed to be enslaved. Slaveholding Anglo-American Loyalists also migrated to Nova Scotia bringing with them about 2,500 enslaved African-Americans. But unlike their free counterparts, these African-Americans remained enslaved until the practice of slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834—meaning, for a few decades, Nova Scotia simultaneously had two distinct Black populations: one whose freedom was protected, and the other whose enslavement was sanctioned.

The Black Loyalists had been promised free land and equality, however these—not unlike other broken promises and treaties made to First Nations by the Crown—were never kept. The area on the southern shore of the Bedford Basin began being settled after the Anglo-American War of 1812, though it was never established as an official, incorporated community. Industrialization soon began to encroach on the small but hitherto self-sustaining community as railway after railway started running through the area. Other facilities unwanted by white communities—a prison, slaughterhouse, an infectious disease hospital, and depository for fecal waste—were located in and around Africville.

Systemic abuse and neglect

Racial inequality kept Africville in an impoverished state. Job opportunities were mostly limited to working as seamen, porters or domestic workers. Education was severely deficient amongst Africville residents, who only had four boys and one girl reach the 10th grade out of 140 children that ever registered in the school. Despite paying city taxes, the residents of Africville went without the basic amenities other towns enjoyed such as proper roads, electricity, health services, or sewage. Even running water was not made available; residents of Africville had to rely on an assortment of wells, the water from which required boiling before drinking or cooking.

Racial inequality kept Africville in an impoverished state. Job opportunities were mostly limited to working as seamen, porters or domestic workers. Education was severely deficient amongst Africville residents, who only had four boys and one girl reach the 10th grade out of 140 children that ever registered in the school. Despite paying city taxes, the residents of Africville went without the basic amenities other towns enjoyed such as proper roads, electricity, health services, or sewage. Even running water was not made available; residents of Africville had to rely on an assortment of wells, the water from which required boiling before drinking or cooking.

While other parts of the city of Halifax, which had amalgamated Africville, was receiving investments for modernization efforts, the racially isolated community of Africville was left to ruin. The final result of 150 years of unequal opportunity, municipal neglect and institutionalized racism was Africville being literally reduced to a slum; a label it officially gained in 1958 after Halifax moved the town dump to the area. In 1962, Halifax City Council decided to expropriate the land and remove the “blighted housing and dilapidated structures” in the interest of “urban renewal.”

Eviction and destruction

Between 1964 and 1967, residents were removed and placed in public housing projects; those who were previously homeowners became renters. Despite their relocation, Africvillians still faced the same problems of inequality and poverty. Social programs that had previously been promised never materialized. The city of Halifax lent their assistance to the people of Africville in such a manner that perfectly illustrates the attitude with which City Hall regarded them: they moved the residents of Africville with the city’s dump trucks.

Between 1964 and 1967, residents were removed and placed in public housing projects; those who were previously homeowners became renters. Despite their relocation, Africvillians still faced the same problems of inequality and poverty. Social programs that had previously been promised never materialized. The city of Halifax lent their assistance to the people of Africville in such a manner that perfectly illustrates the attitude with which City Hall regarded them: they moved the residents of Africville with the city’s dump trucks.

The Africville community was razed to the ground. The houses, school, and the Seaview United Baptist Church—which played an integral role in the social life of the community—were bulldozed to make way for development of the north shore of the Bedford Basin and the A. Murray MacKay Bridge, which crosses the Halifax harbour. Due to the controversy surrounding the events, commercial development did not take place and the waterfront was left intact. In the 1980s, Halifax created Seaview Memorial Park on the old Africville site, which was declared a national historic site in 2002.

Reaction to the apology

Reactions to the apology from former residents and their descendants have been mixed. Most were optimistic and hopeful for the future; former Africville resident Brenda Steed-Ross, who was evicted along with her parents and her infant daughter when she was 18, said she feels “we’re moving forward, not backward.” Rev. Rhonda Britten, a leader within the Black community in Nova Scotia, welcomed the settlement, saying “I know that there are some among us who are wounded, and some among us who bear those scars. But, in spite of all of that, the victory has been won.”

However, not everyone shared Rev. Britten’s optimism. According to a report from CBC News, while most of the crowd offered cheers, there were others voicing dissent, shouting: “Not enough.” Some of the descendants of Africville claimed the settlement was illegal because the Africville Genealogy Society (AGS) didn’t have the right to negotiate on their behalf. One criticism of the agreement is that there is no provision for individual compensation. Eddie Carvey, whose brother Irvine is president of AGS, has been actively raising the issue and protesting since 1994. Along with individual reparations (a word the Canadian press has decidedly avoided using, which I will not), Carvey is also seeking a public inquiry and for the city to return ownership of Africville to its former residents and descendants.

There are apologies and there are apologies

In the interest of reconciliation and restorative justice, formal apologies are more than just gestures; they are vital to building trust between those who have been harmed and those who committed the harm (including the descendants of both sides). They are not to be confused with the actual work to be done to achieve reconciliation and restorative justice, but they are important to begin with. After all, if you can’t start with “I’m sorry,” then what else can you really say that will have any meaning?

For an apology to be a catalyst, it needs to have weight; for an apology to have any weight, it needs to be sincere. But, what if it is incomplete? I do not wish to challenge the sincerity of anyone involved, but I do want to draw attention to the history I have outlined above and the content of the apology below. I want to ask: is it complete?

On behalf of the Halifax Regional Municipality, I apologize to the former Africville residents and their descendants for what they have endured for almost 50 years, ever since the loss of their community that had stood on the shores of Bedford Basin for more than 150 years.

You lost your houses, your church, all of the places where you gathered with family and friends to mark the milestones of your lives.

For all that, we apologize.

We apologize to the community elders, including those who did not live to see this day, for the pain and loss of dignity you experienced.

We apologize to the generations who followed, for the deep wounds you have inherited and the way your lives were disrupted by the disappearance of your community.

We apologize for the heartache experienced at the loss of the Seaview United Baptist Church, the spiritual heart of the community, removed in the middle of the night. We acknowledge the tremendous importance the church had, both for the congregation and the community as a whole.

We realize words cannot undo what has been done, but we are profoundly sorry and apologize to all the former residents and their descendants.

The repercussions of what happened in Africville linger to this day. They haunt us in the form of lost opportunities for young people who were never nurtured in the rich traditions, culture and heritage of Africville.

They play out in lingering feelings of hurt and distrust, emotions that this municipality continues to work hard with the African Nova Scotian community to overcome.

For all the distressing consequences, we apologize.

Our history cannot be rewritten but, thankfully, the future is a blank page and, starting today, we hold the pen with which we can write a shared tomorrow.

It is in that spirit of respect and reconciliation that we ask your forgiveness.

Amongst the recognition that people have suffered and continue to suffer due to wrongdoing on the part of the city council, what are the reasons being given in the formal apology? They acknowledge loss of their houses, loss of their church, and that repercussions “linger to this day”—and this is important to acknowledge. Their loss is tremendous and it is real, and the repercussions continue to manifest 50 years later. But two parts of the apology trouble me, leading me to believe that the greatest loss has been widely overlooked.

For what, exactly?

When they “apologize to the generations who followed” and lament the “lost opportunities for young people who were never nurtured in the rich traditions, culture and heritage of Africville,” flags go up. First question: the generations who followed what? The evictions and bulldozing of homes? Second question: which opportunities do Mayor Kelly, Halifax Regional Council and Halifax Regional Municipality think the young people living in Africville have lost? Their use of the words “nurtured” and “rich” have a certain ironic flair considering Africville was in shambles, with no health services, sewage or running water. Why no apology for that?

Tags: African-Canadian, Africville, Black Loyalists, canada, environmental racism, Halifax, Housing, institutional racism, Nova Scotia, racism, reconciliation, reparations, restorative justice, slavery, systemic racismAuthor: Mike Barber (9 Articles)

Mike Barber is an independent filmmaker with a particular interest in issues surrounding social justice. He is currently directing “A Past, Denied: The Invisible History of Slavery in Canada,” a feature documentary exploring how a false sense of history—both taught in the classroom and repeated throughout the national historical narrative—impinges on the present. It examines how 200 years of institutional slavery during Canada’s formation has been kept out of Canadian classrooms, textbooks and social consciousness. He is currently based in Toronto, Ontario. You can follow him on Twitter at http://twitter.com/mike_barber (@mike_barber) and his film at http://twitter.com/apastdenied (@apastdenied)

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

10 Reasons not to read this

10 Reasons not to read this Not everybody loved hominid fossil “Lucy”

Not everybody loved hominid fossil “Lucy” Black leaders must seize the moment

Black leaders must seize the moment