Lands, sacred spaces part of US human rights review

American Indians, Featured — By Valerie Taliman on April 3, 2010 at 09:33ALBUQUERQUE – The “listening session” held by the U.S. State Department on March 16 at the University of New Mexico Law School drew more than 100 Native leaders, legal scholars and human rights activists, many of whom called on the United States to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Testimony from presenters spanned an array of key issues including rights to self-determination, land, natural resources, sacred sites and religious freedom.

The listening sessions are part of the Universal Periodic Review, conducted every four years by the United Nations Human Rights Council, to examine the United States’ record on legally-binding human rights obligations.

The U.S. has been chastised in the past, and is expected to report on what it has done to implement recommendations made by U.N. human rights bodies.

For example, in 2002, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights ruled the U.S. had violated international human rights laws by seizing the property of Western Shoshone elders Carrie and Mary Dann, and “denying their rights to equality before the law, to be free of discrimination, to a fair trial and to property.”

It was the first time an international body formally recognized that the U.S. had violated the rights of Native Americans.

The ruling supported the Danns’ argument that the U.S. government used illegitimate means to gain control of ancestral Shoshone lands. It also questioned the government’s mishandling of millions of acres of land under the U.S. Indian Claims Commission.

The IACHR found that the ICC claims process – which the U.S. contends extinguished the Western Shoshone rights to most of their land in Nevada – was a flawed process that denied the Danns and other Western Shoshones their human rights.

The IACHR recommended that the U.S. government take steps to provide a fair legal process to determine the Danns’ and other Western Shoshone land rights.

Yet at the listening session, Larson Bill, former chairman of the South Fork Band of Te-Moak, said there has been no progress on recommendations to provide a fair legal settlement for the Western Shoshone.

Again in 2008, the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination formally criticized the U.S. for not doing more to prevent and punish violence against Native women. Justice Department statistics revealed one in three women will be raped in their lifetimes; 86 percent of the rapes are committed by non-Indian men.

Sacred places vs. development

At an afternoon panel on sacred sites, Zuni Governor Norman Cooeyate talked about his tribe’s historic efforts to protect Zuni Salt Lake, a sacred place for many tribes, from desecration and de-watering.

Cooeyate said they fought for decades to reclaim 5,000 acres of land from the federal government to establish a sanctuary surrounding Zuni Salt Lake in 1985.

But in 1996, without consulting the Zuni or any other tribes, the state of New Mexico issued a permit to Salt River Project, the third-largest public power utility in the nation, to build a coal mine within the sanctuary boundaries of the lake.

The Zuni did not find out about the proposed mine or permit for three years, and were appalled to find the lease had been signed by a former lobbyist for coal companies who worked at the Interior Department.

They also learned that hydrological studies indicated strip-mining coal would use 85 gallons per minute of water from the aquifer that feeds Zuni Salt Lake, reducing the water table to a level that would hinder the lake’s ability to produce their sacred salt.

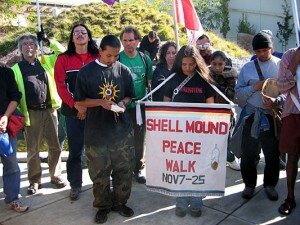

An annual Black Friday protest at Emeryville's Bay Street Mall. The Bay Street Mall was built on top of an ancient Ohlone burial site after years of protest actions by the local Native American community. The construction of the mall unearthed THOUSANDS of human remains, many of which were taken away to landfill in the name of consumerism.

“The songs, ceremonies, gathering of minerals, plants and medicines are the central and irreplaceable elements of my people’s religion and cultural practices,” Cooeyate said. “The power of these sacred ecosystems cannot be duplicated or replaced. We want the United States to uphold our right to protect our sacred places of prayer.”

Mining indigenous lands

Numerous speakers addressed uranium mining and its devastating effects on Native communities in the Southwest.

Manny Pino, a college professor and longtime activist from Acoma Pueblo, said his people have lived with a 50-year legacy of uranium mining, with five communities on the Acoma and Laguna reservations most heavily affected by cancer and early deaths.

The village of Paguate lies within 1,000 feet of the Jackpile Mine, at one time the nation’s largest open-pit uranium mine that produced 24 million tons of ore by operating 24-hour shifts 365 days per year from 1953 to 1982.

“The Atomic Energy Commission was the primary buyer, so uranium from Jackpile went directly to build America’s weapons of mass destruction,” Pino said.

“Our people have had to endure radioactivity in their backyard and wind blowing waste tailings onto our land, our crops, and our children. Even today, more than 1,000 abandoned mines on Navajo lands have not been reclaimed. This is the kind of environmental racism that we have to live with.”

Pino applauded President Barack Obama’s decision to close Yucca Mountain, the proposed high-level nuclear waste site on Shoshone lands in Nevada, and urged nations to stop producing nuclear waste since there is no safe place to store it on the planet.

Carletta Tilousi, a Havasupai Tribal Council member, said she was representing the remaining 600 members of her tribe who live at the bottom of the Grand Canyon.

“We’re fighting to save our sacred Red Butte and our only source of water now that Denison Mines has begun uranium mining on the north rim.”

The Havasupai and Hualapai nations as well as the federal government have called for moratoriums on new mining around the Grand Canyon, but existing claims are exempt on public lands.

That exemption allowed Canadian-owned Denison Mines to begin mining in December 2009, with plans to extract 335 tons of uranium ore per day and haul it more than 300 miles to a mill near Blanding, Utah.

Tilousi said nearly 8,000 new mining claims now threaten northern Arizona, pointing out it would only take one accident to contaminate the Colorado River.

Native inmates’ rights

Lenny Foster, a spiritual advisor and supervisor for the Navajo Nation Corrections Project, spoke of the 30-year struggle to ensure some measure of respect for Native spiritual practices in state and federal prison systems.

“The extreme racism and discrimination toward our spiritual beliefs has made it very difficult for Native inmates to practice and participate in traditional ceremonies,” he said, noting that he has visited 96 state and federal prisons, and counseled more than 2,000 male and female inmates.

He called on the Justice Department to launch an investigation into human rights abuses perpetrated on Native inmates, and to rectify current policies to provide legal protections for the free exercise of religion for incarcerated Indians.

Foster said denial of access to traditional ceremonies is a denial for recovery and spiritual healing.

“The Justice Department has a trust responsibility that encompasses criminal justice, corrections and human rights, including a legal obligation to protect traditional Native spiritual practices.”

Speaking as a private citizen, attorney Donovan Brown said, “There are many federal laws whose intent appears to protect Native American sacred places and religious activities. These laws, however, have been proven useless.”

Brown said Native sons and daughters have served in every branch of the United States military and have unselfishly given their lives on foreign soil fighting for the human rights of other peoples.

“They should not be required to return to their lands only to be denied the inherent and fundamental right of self-determination, to freely determine their own destiny, to pursue their economic, social and cultural development, and to live on and manage their lands free of external interference, encroachment and occupation.”

Author: Valerie Taliman (6 Articles)

Valerie Taliman, Navajo, is president of Three Sisters Media, which offers publishing, social media and public relations services. She is also an award-winning journalist specializing in environmental, social justice and human rights issues. She is based in Albuquerque, N.M. Contact her at [email protected].

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

Civil disobedience for beginners

Civil disobedience for beginners Demanding to be seen and heard: Latino immigrant organizing in Houston

Demanding to be seen and heard: Latino immigrant organizing in Houston