Why Libertarians (and Rand Paul) are wrong about The Civil Rights Act

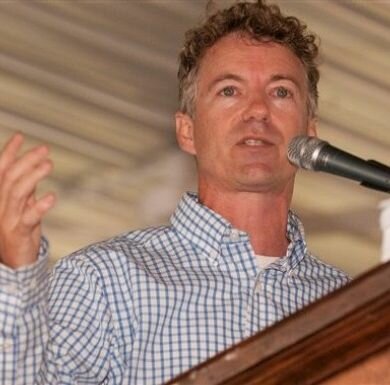

Talk About Race — By Stephen Menendian on May 27, 2010 at 06:01Following his tea-party insurgent Senate primary victory over the establishment Republican candidate in Kentucky, Rand Paul created waves when Rachel Maddow forced him, uncomfortably, to admit his opposition to parts of the Civil Rights Act. To many in the civil rights community, and to the political center, this comes as a shock.

It shouldn’t be.

For years, libertarians opposed government interference with private business, whether that means opposition to environmental regulation, labor laws, or anti-discrimination laws. The son of libertarian presidential candidate, Ron Paul, it’s not surprising that Rand Paul also believes those things. Rand Paul has made it clear that he’s not in favor of a repeal of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and that he supports the vast majority of it. What’s the problem then? He specifically opposes the provisions that prohibit discrimination in what are known as ‘public accommodations,’ which are really private businesses such as hotels, movie theaters, or lunch counters.

His view is that, while private racial discrimination is anathema and despicable, it’s not something that the government should regulate. His argument, a libertarian argument, is that regulating private discrimination goes beyond the sphere of government authority. In addition, he argues, private discrimination is better regulated by market forces. In his view, and in the view of many libertarians, the private market would regulate and weed out businesses that discriminate, since business with what economists call a ‘taste for discrimination’ would lose patrons.

They are wrong.

They are wrong, first and foremost, because they miss the point. Discrimination isn’t about economic efficiency; it’s about morality, fairness, and a basic conception of equality; it’s about justice.

There is a broad literature in economics about the efficiency of slavery, and whether, in time, the institution of slavery would have withered and died, as it did in many northern states. This literature, while fascinating, is beside the point. The abolition of slavery was a moral imperative, not an economic one. The abolitionist movement emphasized the contradiction between the values of the young nation and the institution of slavery, a contradiction which the founding fathers struggled with.

Similarly, the prohibition of private discrimination in ‘public accommodations’ is a moral issue, as are a host of regulations we impose on business. For example, we prohibit businesses from exploiting child labor based on a moral judgment which says that it is wrong. At the turn of the 20th Century, growing opposition to child labor in the North caused many factories to move to the South, until national child labor laws were passed.

Rand Paul’s viewpoint, that private discrimination on the basis of race should not be illegal, would seem to suggest that he opposes the 1968 Civil Rights Act (aka the Fair Housing Act) in its entirety, since, unlike the Voting Rights Act, the Fair Housing Act targeted private individuals, not states. And, his position would also seem to permit discrimination not just on the basis of race, but on the basis of sex, religion, familial status, and disability. Someone should ask him if he would repeal the Fair Housing Act, since that is the logical consequence of his position. Then, he wouldn’t be able to hide behind state-targeted provisions.

But there are also other reasons which make it wrong. Rand Paul claims that “intent of the legislation… was to stop discrimination in the public sphere and halt the abhorrent practice of segregation and Jim Crow laws.” He’s wrong. The Civil Rights Act was not simply targeted at state sponsored behavior. After all, the Jim Crow laws and the public segregation and discrimination embodied in them were a manifestation of the values of the society, and the individuals within it.

In the South, segregation and Jim Crow were an expression of the values of the society, of the extant social norms and mores. Those values were also present in the north, except that segregation was more a matter of practice and custom than legislation. The Civil Rights Act targeted those laws, without question, but it also targeted the practices, values, norms, and prejudices from which those institutional forms of discrimination were an expression. It targeted the North, not simply the South. Rand Paul and other libertarians are attempting to rewrite history by suggesting that the Civil Rights Acts were merely targeting the institutionalized expression of these values. The Fair Housing Act (aka Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act), which targeted private housing discrimination, belies this point.

But even more deeply, the private/public distinction at the heart of the libertarian argument is flawed. As Justice Kennedy put it in his concurrence in Parents Involved: “The distinction between government and private action, furthermore, can be amorphous both as a historical matter and as a matter of present-day finding of fact. Laws arise from a culture and vice versa. Neither can assign to the other all responsibility for persisting injustices” (emphasis added).

He’s absolutely right.

In fact, the relationship between individual racist attitudes and law is at the heart of Chief Justice Taney infamous Dred Scot opinion. Chief Justice Taney held that persons of African descent were not – and could never be – citizens of the United States because white folks, not simply white governments, regarded them as inferior. It was the way in which white people in their private pursuits regarded black folk, not simply how states and white governments regarded them that was decisive:

Tags: civil rights act, Politics, Rand Paul“[Persons of African descent] had for more than a century before been regarded as beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations; and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit. He was bought and sold, and treated as an ordinary article of merchandise and traffic, whenever a profit could be made by it. This opinion was at that time fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the white race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute; and men in every grade and position in society daily and habitually acted upon it in their private pursuits, as well as in matters of public concern, without doubting for a moment the correctness of this opinion.”

Author: Stephen Menendian (12 Articles)

Stephen Menendian is the senior legal research associate at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at the Ohio State University. Stephen directs and supervises the Institute’s legal advocacy, analysis and research, and manages many of the Institute’s most important projects. His principal areas of advocacy and scholarship include education, civil rights and human rights, Constitutional law, the racialization of opportunity structures, talking about race, systems thinking and implicit bias. Stephen co-manages the Institute’s Integration Initiative to promote diversity, reduce racial isolation, improve funding equity, and close the achievement gap in our nation’s public schools. Stephen works closely with school districts and other educational entities to develop successful integrative measures and implement practices that produce educational excellence for all students. Stephen also co-manages the Institute’s Fair Recovery Project (www.fairecovery.org) to ensure that federal initiatives and investments promote equity and equal opportunity for all, and that jobs and foreclosure relief target those who have been hit hardest by the economic downturn. Stephen also directs the Institute’s Affirmative Action Project and was the lead author of the Institute’s Structural Racism Report to the CERD Committee to improve US treaty compliance with the Convention for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination. Recent scholarly publications include Parents Involved: The Mantle of Brown, the Shadow of Plessy for the University of Louisville Law Review and the forthcoming Remaking Law: Moving Beyond Enlightenment Jurisprudence for the St. Louis University Law Review. Stephen occasionally guest-lectures at the Moritz College of Law, and co-taught The History and Culture of Race and Law, a seminar at Wayne State University Law School, in the fall of 2009. Stephen is a licensed attorney and a member of the Ohio State Bar Association, the Columbus Bar Association, and the American Bar Association. He also serves on the board of directors for Americans for American Values. He earned his J.D. from the Moritz College of Law, Ohio State University and a B. A. in Economics from Ohio University, where he graduated summa cum laude.

Share This

Share This Tweet This

Tweet This Digg This

Digg This Save to delicious

Save to delicious Stumble it

Stumble it

One year after Haiti earthquake, corporations profit while people suffer

One year after Haiti earthquake, corporations profit while people suffer The people or the pulpit

The people or the pulpit John Mayer's longing for blackness is a"Very" wide-open window into U.S. race relations

John Mayer's longing for blackness is a"Very" wide-open window into U.S. race relations

3 Comments

Goodness, that is a long long bio you’ve created . . .