African human rights defenders or colonialists? Seeking justice in Equatorial Guinea

A few years ago I had the privilege of visiting Equatorial Guinea, a small country on the Central West African coast. In the capital city of Malabo I met incredible women and men persevering to feed, clothe, and educate their children on less than on dollar per day. Most suffered from malaria and typhoid fever, lived in homes lacking running water and with sporadic electricity, and were surrounded by overflowing dumpsters with garbage piled higher than their houses. I observed elementary schools in which single teachers were responsible for educating several grades in one room, lacking the necessary materials to succeed, and secondary schools without bathrooms.

Outside the capital I toured a hospital whose maternity ward had beds without mattresses and birthing equipment so decrepit it was abundantly clear why most women choose to deliver at home. I spoke to a nurse who said another hospital where she worked had just broken its last remaining thermometer and was desperate for bandages, alcohol, sutures, and other basic medical supplies.

While troubling, these conditions are perhaps not remarkable in an impoverished, forgotten African nation. The problem is that Equatorial Guinea is neither impoverished nor forgotten. It is one of the largest oil producers in Africa, exporting about 400,000 barrels of oil every day. Its income per capita is on par with countries like Japan and France, yet its Human Development Index remains in line with that of Guatemala. For over thirty years Equatorial Guinea has been governed by a ruthless dictator, President Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, whose family has uniquely benefitted from the country’s growing wealth.

For these reasons, this spring a group of Equatoguineans in exile organized to oppose the recent creation of the UNESCO‐Obiang Nguema International Prize for Research in the Life Sciences, funded by President Obiang to the tune of $3 million:

“Some of us are in exile today because the government of Teodoro Obiang Nguema unjustly persecuted, arbitrarily detained, threatened directly or indirectly, or denied us entry into Equatorial Guinea. Others remain in exile because of pending judgments against us, entered during our absence from Equatorial Guinea, for expressing our political views or denouncing the government’s human rights record. In short, under the current regime there are no freedoms of expression, association, or assembly in Equatorial Guinea.”

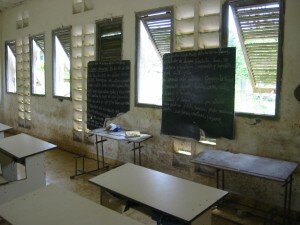

They argue that, in this context, the prize amounts to international endorsement of Obiang’s systematic political repression, his deprivation of the most basic needs of his people, and his blatant use of public funds for personal gain. They believe the funds should be used instead “for the purchase of books, benches, and other such rudimentary educational materials” for students in Equatorial Guinea, in the hopes that the country may one day produce scientists and other professionals capable of becoming future recipients of international prizes. Their move has garnered international attention, receiving support from over 35 nongovernmental organizations and from hundreds of scientists, journalists, scholars, and others asking UNESCO to cancel the prize.

Under mounting pressure, the Equatoguinean government has fired back, calling those speaking out against the prize “colonialist, discriminatory, racist, and prejudiced” and depicting the campaign as one advanced by uninformed Western organizations “that wouldn’t even know how to locate our country on a map.” In the face of these claims, many of UNESCO’s member countries who initially opposed the prize have recoiled, wary of appearing anti-African or colonialist. African member states, who should be leading the charge to demand greater accountability from one of the continent’s most notorious authoritarians, instead appear to be supporting the prize. Thus, in a calculated distortion of reality, accusations of neocolonialism and racism now threaten to erase the agency of the very Equatoguinean activists who have led the campaign from its start.

Tomorrow UNESCO’s executive board will meet to discuss the growing global controversy and decide whether or not to accept Obiang’s dirty money. May they have the strength to stand up for what is right—not on the side of an shameless dictator, nor in lock step with Western “colonialists,” but in honor of UNESCO’s mission to promote education, science, culture, and human rights, and in shared conviction with Equatoguineans who envision a more just future for themselves and their people. (And should UNESCO disappoint, I invite all potential prize recipients to act upon their principles and join the movement for a more just Equatorial Guinea by publicly rejecting the award.)

YOU CAN HELP! ACT NOW by sending an email to [email protected] (David Killion, U.S. Embassador to UNESCO) and [email protected] (Irina Bokova, Director General of UNESCO) asking UNESCO to cancel the Obiang Nguema International Prize for Research in the Life Sciences.

###

Photos by Angela Stuesse

Author: Kirwan Institute (427 Articles)

COMMENTS