Canadian government apologizes to Inuit for the past, while screwing Barriere Lake Algonquins in the present

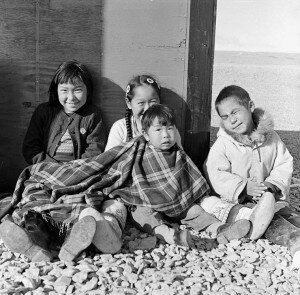

During the 1950s, the Canadian federal government enacted policies to relocate Inuit families from their homes in Inukjuak, located in northern Quebec, to the remote High Arctic areas of Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord. Their traditional homeland provided all they needed to sustain, including plenty of caribou and other game to hunt, which was a stark contrast from the veritable wasteland that the Inuit found themselves in when they arrived.

During the 1950s, the Canadian federal government enacted policies to relocate Inuit families from their homes in Inukjuak, located in northern Quebec, to the remote High Arctic areas of Resolute Bay and Grise Fiord. Their traditional homeland provided all they needed to sustain, including plenty of caribou and other game to hunt, which was a stark contrast from the veritable wasteland that the Inuit found themselves in when they arrived.

It became immediately clear that they had been duped by the government into accepting a barren arctic desert as their new home. The effects of the relocation were devastating. Compounding the issue of sparse hunting opportunity was the federal government’s failure to provide the people with any form of housing, leaving the Inuit to try to survive in Igloos and tents. The struggle for food and shelter in the desolate north left many dead.

On August 18, 2010—five decades after relocation—Canada’s Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development John Duncan officially apologized on behalf of the federal government. “The government of Canada deeply regrets the mistakes and broken promises of this dark chapter of our history and apologizes for the High Arctic relocation having taken place,” said Duncan as he stood before a group of Inuit residents in Inukjuak, Quebec. “They were not provided with adequate shelter and supplies. They were not properly informed of how far away and how different from Inukjuak their new homes would be, and they were not aware that they would be separated into two communities once they arrived in the High Arctic … Moreover, the government failed to act on its promise to return anyone that did not wish to stay in the High Arctic to their old homes.”

The apology appears to be widely welcomed as a step towards healing by those in the community who were affected by the relocations. But as contrite as the Indian Affairs Minister was in his apology, other events currently unfolding make it painfully obvious that the federal government has simply not learned from their many, many mistakes.

Doing right, yet getting it wrong

On February 24, 2010 the mayor of Halifax, Nova Scotia apologized for the evictions and razing of the African-Canadian community of Africville during the 1960s. At that time, I laid the charge that an apology for the “what” and the “how” that happened in the past, but which does not address the “why,” is in itself a failure. This is especially true if the same underlying “why” still persists after the apology is made. While Duncan’s apology to the Inuit has been a very long time coming and is important to the people affected by the federal government’s interference and broken promises, it still amounts to a failure because the government is doing nothing to change the underlying behavior for which it has apologized.

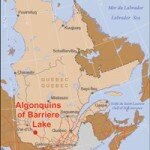

While Duncan was delivering his apology to the Inuit of Inukjuak, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) was going forward with the draconian act of imposing a new Chief and Council on Barriere Lake, an Algonquin band located on unceded territory in Quebec about 300 kilometers (190 miles) north of Ottawa, Ontario. The community of Barriere Lake, who have a long established traditional system of self-governing called the Mitchikanibikok Anishinabe Onakinakewin, have widely denounced the decision by INAC. Casey Ratt, who is the Band Council Chief appointed by INAC, has refused the position.

While Duncan was delivering his apology to the Inuit of Inukjuak, the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (INAC) was going forward with the draconian act of imposing a new Chief and Council on Barriere Lake, an Algonquin band located on unceded territory in Quebec about 300 kilometers (190 miles) north of Ottawa, Ontario. The community of Barriere Lake, who have a long established traditional system of self-governing called the Mitchikanibikok Anishinabe Onakinakewin, have widely denounced the decision by INAC. Casey Ratt, who is the Band Council Chief appointed by INAC, has refused the position.

The actions of INAC are not only undemocratic, they are also a violation of section 35 of the Canadian Constitution Act which the Canadian government has affirmed protects “the inherent right of self-government as an existing Aboriginal right.” The reason that the INAC feels that they are entitled to impose their decision concerning such matters upon the Algonquins of Barriere Lake—and the reason the federal government gives INAC a pass at circumventing the Constitution—is found buried in the federal legislation concerning government policy with regards to First Nations. I am speaking specifically about section 74 of the Indian Act, which allows the Minister of Indian Affairs to impose its own electoral system and its results on a community “whenever he deems it advisable for the good government of a band.”

It is widely believed that the reasoning behind INAC invoking this obscure section of the Indian Act—a provision which has only been used three times in Canadian history, the last being in 1924 against the Haudenosaunee government—is, in the words of community spokesperson Marylynn Poucachiche, “to sever our connection to the land, which is maintained by our traditional political system. They don’t want to deal with a strong leadership and a community that demands the governments honour signed agreements regarding the exploitation of our lands and resources.” It’s an old tactic we’ve seen many times before: destabilize, install, control. In this particular case, the government’s end goal is to exploit the community’s land.

When it comes to fully understanding the many complicated issues facing the First Nations, it is almost impossible to do so without also discussing the aforementioned Indian Act and understanding its history. So let’s dive in together…

An Act Respecting… whom?

For those who are not familiar, the ironically titled An Act Respecting Indians (R.S., 1985, c. I-5)—commonly known by its legal short name as the Indian Act—is a federal statute that originated in 1876. It is the legal embodiment of the government’s long standing policy to coerce the First Nations people (whom the Act identifies as “Indian”), through paternalistic and oppressive policies and practices, to assimilate into the dominant white British-Canadian culture. Historically the Indian Act has been, in effect, a blueprint for apartheid and cultural genocide.

For those who are not familiar, the ironically titled An Act Respecting Indians (R.S., 1985, c. I-5)—commonly known by its legal short name as the Indian Act—is a federal statute that originated in 1876. It is the legal embodiment of the government’s long standing policy to coerce the First Nations people (whom the Act identifies as “Indian”), through paternalistic and oppressive policies and practices, to assimilate into the dominant white British-Canadian culture. Historically the Indian Act has been, in effect, a blueprint for apartheid and cultural genocide.

As the legal thumb used by the federal government to systematically oppress the First Nations people, the Indian Act, at different times through different amendments, has been used to shape and control every aspect of their lives by, for example: placing bans on traditional ceremonies and dances (1885); allowing the forced removal of Indians from reserves near towns with more than 8,000 residents (1905); allowing municipalities and companies to expropriate portions of reserves, without surrender, to be used for public works such as roads and railways (1911); requiring western Indians to obtain official permission from the government before appearing in “aboriginal costume” in any “dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant” (1914); preventing anyone, whether Indian or not, from soliciting funds for First Nations legal claims without a special license from the Superintendent-General, thereby preventing First Nations people from being able to pursue land claims (1927). In 1930 an amendment was added to make it an offense for pool hall owners to allow entrance to a First Nations person who “by inordinate frequenting of a pool room either on or off an Indian reserve misspends or wastes his time or means to the detriment of himself, his family or household”; the list goes on and on.

1 2

Most Recent

Recent Comments

- Blog News- Left and Right Views » Race-Talk » Blog Archive » Michael Barone gets his facts wrong on Michael Barone gets his facts wrong

- Acknowledging Difference, not Defeat: A Racial Justice Perspective on the Medicaid Debate | health justice NYC on Acknowledging difference, not defeat

- Links of Great Interest: Bring Amina home! — The Hathor Legacy on In prison reform, money trumps civil rights

- Race-Talk » Blog Archive » President Barack Obama, Dred Scott: A … | Barack Obama on President Barack Obama, Dred Scott: A case of domestic terrorism

- In prison reform, money trumps civil rights « Politicore on In prison reform, money trumps civil rights

Search in Archive

Favorite Blogs

What is Race-Talk?

The Race-Talk is managed and moderated by the staff at the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity and is open to all respectful participants. The opinions posted here do not necessarily represent the views of the Kirwan Institute or the Ohio State University.

Our goal is to revolutionize thought, communication and activism related to race, gender and equality. Race-Talk has recruited more than 30 extraordinary authors, advocates, social justice leaders, journalists and researchers who graciously volunteered their expertise, their passion and time to deliberately discuss race, gender and equity issues in the US and globally.

COMMENTS